Reading the Bible.

It is hard to speak about private daily devotions, because they are, just that, private. In some ways it is an intimate thing. It is better to be doing it than talking about it. Sometimes sharing on the subject can be singularly unhelpful. When hearing about the person who gets up at 5am and reads through the whole of Jeremiah, one of the Gospels and Psalm 119, before spending two hours in prayer, for lists of people in their prayer book, you are tempted to say “Oh come on, get a life”. They are not usually people who have been up half the night dealing with a vomiting child, struggling to get a teenager out of bed, living with a flatmate who left the kitchen in a tip, coping with a husband on the drink, caring for a demanding elderly relative or someone who has to work night shifts. These testimonies are given with an encouraging intention but the effect is demoralisation. You might just want to give up. So we are treading on thin ice, walking over glass here. It’s just a shame that we find it so hard to talk or enquire about. In all my Christian life no one has asked me “How are you finding your daily reading of the Bible, Crawford?” I wish they had. There again, I guess I might have told them just to mind their own business.

I have been a Christian a follower of Jesus for as long as I remember. So it’s maybe quite strange and even shocking, (it’s shocking to me) that it is only in the past year or so, that I have finally learned something about the practice of daily bible readings. Something I should have known years ago. It was not that I was never taught, more that I was never listening.

With the strong influence of Scripture Union, Churches and other organisations, I have tried to follow schemes compiled to help us find a way through the bible. Often these would be supplied with helpful notes and encouragements to think through the passage as well as to see how this impacts our life with pointers for prayer. But I always found the imposition of this kind of discipline from outside hard to deal with, which probably says more about my stubbornness than anything else. The critical point came when I would embark on a scheme with very good intentions and then fail and fail again and it led to a spiral of discouragement and resignation. That way of doing things clearly works for so many people, maybe be most Christians. I don’t know. But they didn’t work for me.

It was when a wise pastor told me, while in my teens, that the Christian life was an integrated life and not a disconnected deconstructed series of activities with boxes to tick, that the light dawned. A “quiet time” could be useful, but not if it became just another thing to do. Something to gain points and help make you feel better about yourself. That, like much of what this pastor said was liberating and I felt a tremendous freedom and a new delight in reading God’s word. Yet in this freedom there still needed to be some discipline, some order, some plan, some direction. It was easy to find yourself in the books of the bible that you liked, parts that suited your temperament. For me it was the Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Mark’s Gospel and Paul’s “happier” letters to the Thessalonians and Philippi. I didn’t go naturally to Romans or Ephesians, avoided Hebrews and pretty well ignored large swathes of the Old Testament. It was also easy to pick out nice helpful bits here and there, often quite out of context.

So over the years my bible reading has at best been sporadic, reading to prepare for something: preaching, leading a group, giving a talk, a children’s’ holiday club, working on material for a song, or anything that took my fancy. Please don’t get me wrong. You do learn so much when you are trying to teach others. Sometime you only fully grasp a truth when you are trying to communicate with others. But the practice of daily bible reading, unconnected with any preparation or activity, for me, was a very hit and miss affair and there was no pattern to it.

So what has changed and what made the difference?

Well a number of things. Coming to the church we now belong to, was one of them. It was not the reason for coming, (that is another story) and in a way there was nothing especially different about it, but it was under the ministry of David Robertson that I found a new focus on the Bible as God’s word. It was not that the Bible was not central in the churches where we had previously belonged. It was. But here, for me, it took on a new dimension. It was moving up a gear. It was being pulled nearer to where I should have been. It was having my ears syringed. It seemed that the whole of the church’s life was soaked in the whole of God’s word. It was never an add-on.

Another was reading a book by Sinclair Ferguson “From the mouth of God”, which I can’t commend highly enough to anyone who wants to read the bible. It is straightforward, easy to understand, follow and demonstrates with great clarity why we can trust the Bible, how we read it and how we can apply it to every aspect of life.

Another was a comment by Dominic Smart in a monthly letter to his congregation in Aberdeen. It was that reading the bible should be first before anything else. Hearing what God has to say should be before listening to anyone else.

Another was something Billy Graham said in a video, following a campaign some years ago, when he described his daily practice of reading a psalm each day to re-orientate himself with God, and reading the Proverbs to relate to the world we live in.

Another was something from a book, I didn’t read, but which was quoted to me, on meditation and the serious contemplation of Scripture.

So this is what I try and do:

I try, each day, to make God’s word the first thing that enters my mind: before reading what other people say about it, before listening to, or reading the news, before hearing the musings of clever people or the prattling of a radio commentator, before social media, before listening to music, because music itself speaks to you. Before all these I want to hear God’s voice.

So I read through books of the Bible, generally a chapter a day, with the intent of covering and continuing to cover the whole: a gospel, one of Paul’s letters, one of the prophets, a book of history or wisdom or from the Pentateuch. Then I read a Psalm, working consequently through the ancient songbook and finally I read a chapter from the book of Proverbs which is helpfully divided into 31 so you know where you are in the month. The practical wisdom alone in the later speaks right into the day whether it is work or any other activity.

Then I get outside for a walk: for the the fresh air, to meditate, to let the words, the thoughts, the pictures, the poetry, the wisdom soak into my being and to wonder at the reality of God’s presence and bask in his love.

That is what I try to do but even as I write this, it sounds almost formulaic, prescriptive and the very thing I was railing against earlier in this piece. But I know that the experience, the reality and the blessings that pour from this purposeful habit, however that habit is integrated in a life, cannot be measured.

Crawford Mackenzie

I was reminded, this week, of a series of programmes produced by Radio Scotland, that I listened to some years ago entitled “The people’s war”. It was a simple collection of interviews and voices of ordinary folk who had lived through and survived the Second World War. They were not soldiers, officers, politicians or important players but folk caught up in an event quite beyond their control. I was deeply moved by the simple ordinariness of the stories in the face of great horrors. I wrote to the BBC afterwards expressing my appreciation and asking if they would repeat the series. They said they had no plans to do so and I have tried several times to find the recordings on archives with no success. But I remember the stories very clearly.

I was reminded, this week, of a series of programmes produced by Radio Scotland, that I listened to some years ago entitled “The people’s war”. It was a simple collection of interviews and voices of ordinary folk who had lived through and survived the Second World War. They were not soldiers, officers, politicians or important players but folk caught up in an event quite beyond their control. I was deeply moved by the simple ordinariness of the stories in the face of great horrors. I wrote to the BBC afterwards expressing my appreciation and asking if they would repeat the series. They said they had no plans to do so and I have tried several times to find the recordings on archives with no success. But I remember the stories very clearly.

I don’t where I heard it, or from whom, but it was about a wise Nigerian pastor who was preaching to a congregation of restless young men in a town north of Abuja on the Jos plateau. They were disaffected, frustrated and angry young men and he was struggling to get through to them and beginning to lose their attention. Some had been drawn to a new awakening in the old religions in the demonstrable power of the witch doctor, Some were stirred by Marxism while others were beginning to see Islam as the one true religion.

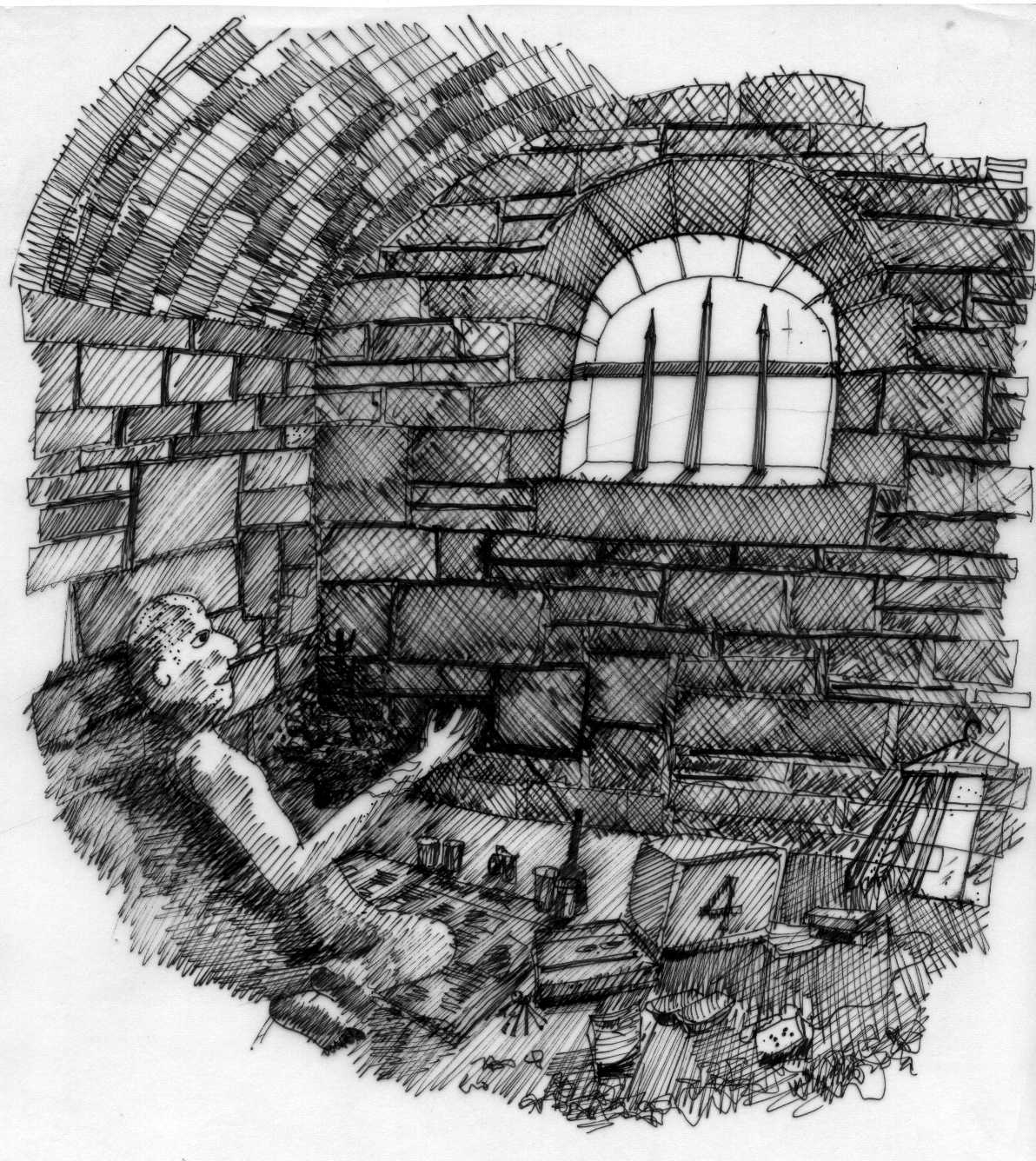

I don’t where I heard it, or from whom, but it was about a wise Nigerian pastor who was preaching to a congregation of restless young men in a town north of Abuja on the Jos plateau. They were disaffected, frustrated and angry young men and he was struggling to get through to them and beginning to lose their attention. Some had been drawn to a new awakening in the old religions in the demonstrable power of the witch doctor, Some were stirred by Marxism while others were beginning to see Islam as the one true religion. The prison that I used to visit was just a few miles down the road. With other volunteers we went there every Wednesday evening, to meet the men who had gathered, to share coffee and tea, to chat to study the bible and to pray together. It was the highlight of my week. There was something special and refreshing about these times. We were able to talk about real things, about things that mattered about families, sorrow and regret, loneliness and fear, life and death, heaven and hell. There was no need to pretend. One of the officers was very supportive of us and on the way in one night he took me aside and said. “You know what you folk do is really good. What these guys need is religion” I didn’t have the wit to respond to him then but I thought about it afterwards. Religion was the last thing these guys needed. They needed a Saviour. We need a Saviour. One of the amazing truths that this week reminds us of is that there is that Saviour.

The prison that I used to visit was just a few miles down the road. With other volunteers we went there every Wednesday evening, to meet the men who had gathered, to share coffee and tea, to chat to study the bible and to pray together. It was the highlight of my week. There was something special and refreshing about these times. We were able to talk about real things, about things that mattered about families, sorrow and regret, loneliness and fear, life and death, heaven and hell. There was no need to pretend. One of the officers was very supportive of us and on the way in one night he took me aside and said. “You know what you folk do is really good. What these guys need is religion” I didn’t have the wit to respond to him then but I thought about it afterwards. Religion was the last thing these guys needed. They needed a Saviour. We need a Saviour. One of the amazing truths that this week reminds us of is that there is that Saviour.

A morning walk through Magdalen in the eye of the storm under a clear blue sky, with a twin prop glinting on its descent to the west, the Edinburgh train slowly snaking over the river, a dog walker in the distance and a thrush in song just feet away in the hawthorn, is shouting to me “Spring” . But It could be an Indian summer, that surprising, delightful experience when after the dark depressing days, of winter you are treated to an unseasonal and unpredicted period of unbounded joy and colour, freshness, stillness and the unrestrained chatter of life.

A morning walk through Magdalen in the eye of the storm under a clear blue sky, with a twin prop glinting on its descent to the west, the Edinburgh train slowly snaking over the river, a dog walker in the distance and a thrush in song just feet away in the hawthorn, is shouting to me “Spring” . But It could be an Indian summer, that surprising, delightful experience when after the dark depressing days, of winter you are treated to an unseasonal and unpredicted period of unbounded joy and colour, freshness, stillness and the unrestrained chatter of life.